Sir Henry Barton

• Yeoman of the King’s chamber by 13 July 1400.

• Purveyor of furs and pelts and skinner for the King’s household 5 Jan. 1405-22 May 1433.

• Sheriff, London and Mdx. Mich. 1405-6.

• Alderman of Farringdon Ward Without by 14 Apr. 1406-aft. 21 Feb. 1412,

• Cornhill Ward 12 Mar. 1412- d; mayor, London 13 Oct. 1416-17, 1428-9.

• Tax collector, London Dec. 1407.

• Collector of tunnage and poundage, London 12 June 1408-24. Jan. 1410, of the wool custom 26 July 1410-28 Feb. 1416.

Biography

If, as seems likely, it was Henry Barton, the distinguished London alderman, who obtained custody of the manor of Barton (now Barton Hartshorn), Buckinghamshire, in April 1421, then his ancestry can be traced back to the 12th century. Land elsewhere in the area had passed into the hands of his nephew and heir, Thomas Barton, by 1437, so there is a strong possibility that he came from a local family which had lived in Barton for over 200 years.

Henry Barton is first mentioned in December 1391, when he offered joint sureties of £300 in Chancery on behalf of a Londoner named William Mildenhall. The poor of the Suffolk village of Mildenhall were remembered by Barton in his will, probably because of some long-standing personal association with the place which may have come through his mother. He was a party to various property transactions in East Anglia at a later date, and did business there from time to time.

John of Guant

Barton began his career as an official in the household of Queen Anne, consort of Richard, with a life annuity of £5 charged upon the manor of Isleworth, Middlesex. On her death in 1394, Richard gave instructions that the annuity should still be paid — as did Henry IV in the period immediately following his coronation. The sudden change of ruling dynasty worked to Barton’s advantage, since he had previously been employed as a skinner by John of Gaunt, the new King’s father, and was now shown every mark of royal favour. He was one of the yeomen of the chamber who remained in attendance upon Richard’s widow, when Henry IV set out on his Scottish expedition of 1400; and in January 1405 he became the first skinner to be retained officially on the staff of the Wardrobe, partly in recognition of his services to the house of Lancaster. He wore the livery of a sergeant of the Wardrobe and drew a wage of 1s. a day for the next 28 years. The opportunities for financial gain were in theory considerable, since Barton himself supplied most of the pelts used at court, although he was increasingly obliged to do so on credit with little hope of immediate repayment. The keeper of the Great Wardrobe already owed him £569 by Michaelmas 1406; he supplied furs worth £217 over the following year, and claimed a further £80 in expenses. An assignment of £782 was made to him from the Exchequer in January 1408, but not all his tallies were honoured, and some of the money (plus a new debt of £184) was still due in May 1409. Even though he then seems to have been paid off in full. In April 1414, while still collector of the wool custom, Barton paid £107 for 45 sacks of wool which had been seized by royal agents at Newcastle.

King Henry V

Henry V certainly seemed disposed in his favour: His petition to the Parliament of 1415 for help in extracting a payment of £333 from the late King’s executors was successful; and six years later he obtained an allocation of £600 from the profits of the lordship of Newport. Unfortunately, however, this act of royal generosity was more apparent than real, since hardly any revenues had been collected there for a long while. Largely because of the worthless tallies given to him during Henry V’s last years, the Crown was £2,100 in Barton’s debt by December 1423. Some four years earlier, in a vain attempt to obtain preference at the Exchequer, he had actually offered a silver cross worth £45 to William Kinwolmarsh, the then under treasurer, who could only plead poverty on the part of the King, and with unusual honesty decline the bribe. The repayment of a royal ‘loan’ of £1,200 advanced by Barton was finally authorized in April 1424, albeit under less than ideal conditions.

Rather less is known about Barton’s other business affairs and connexions. In July 1396 he was suing one William Brewer, who had allegedly left his service before the agreed term. Two years later we find him acting as a surety in Chancery, a service which he appears to have performed only once more during his lifetime. He again went to law in March 1405, this time because of an assault upon either his person or property by six Londoners, but he was himself being sued by two of his fellow citizens in November 1412. Some years later, in December 1423, Joan Cogenhoe was found guilty of forging a recognizance in Barton’s name: despite her attempts to rob him of £100, he intervened to have her punishment made less severe.

Although it is now impossible to determine the full extent of Barton’s holdings in London, he was clearly one of the city’s major property owners, with an annual rental of £21 as early as 1412. The bulk of Barton’s possessions lay in the parishes of St. Mary Aldermary (where he appears to have been active as a feoffee), All Hallows Bread Street, and St. Alphage Wood Street. He also owned a tenement in West Cheap, and at some point before 1420 occupied another tenement and a shop in the parish of St. Stephen, Walbrook. His largest single purchase was made in October 1419, when he bought the late Drew Barantyn’s great house in the parish of St. John Zachary, together with other premises in that area. Understandably, a large number of Barton’s fellow citizens were anxious to retain his services as a feoffee-to-uses. He was a party to innumerable conveyances of property in the City, often with William Cromer. Barton did not often become involved in such transactions outside London, but he held a joint title to the Norfolk estates of Robert, Lord Poynings (d. 1446), and to the manor of ‘Marlawes’ in Middlesex, which was settled on him and other feoffees by his friend, Richard Marlow. We do not know exactly what his interests were in East Anglia, although they may well have been considerable. In August 1410, William Clifford, a local landowner, granted Barton an annual rent of 25 marks payable over the next 20 years from his property in Norfolk and Suffolk.

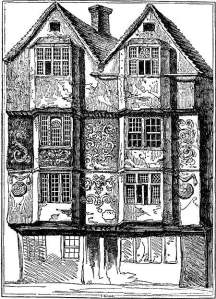

15th Century London house

Despite his commitments in the royal household and the demands made upon him as a rentier, Barton found time to pursue a long and active civic career, being one of the few Londoners who was rich enough to hold the office of mayor twice during the early 15th century. Henry Barton was called upon to perform his first official duty in October 1402, when he was named, but not chosen to serve, as a juror from Cordwainer Street Ward at the husting court. He became sheriff three years later, and held aldermanic rank continuously from April 1406 until his death.

During his later years he was frequently chosen to arbitrate in mercantile and property disputes brought before the mayor and aldermen. He attended at least 14 of the parliamentary elections held in London between the autumn of 1414 and 1432; and in 1425 he was made one of the keepers of the common seal. The city journals for 1416 to 1429 show that he was regularly present at meetings of the common council and court of aldermen.

Barton died between 11 Apr. and 18 June 1435, and was buried in the charnel house at St. Paul’s, where he and two other skinners (one of whom was named Robert Barton) lay ‘entombed with their images of alabaster over them, grated or coped about with iron’. Since he left no children, Barton was able to set aside a major part of his property and an impressive collection of plate for pious and charitable uses.

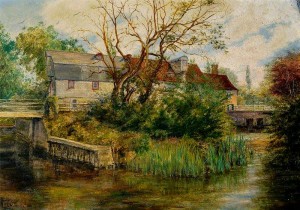

(c) Mildenhall and District Museum; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

by F. J. N. Statham

• Oil on board, 35 x 48 cm

• Collection: Mildenhall and District Museum

Shared Memories…

The river Lark is perhaps the ‘goldilocks’ of all East Anglian rivers. It has a fairly constant flow of water throughout the year; but most importantly between Bury St Edmunds and MiIdenhall. It gently falls about fifty feet, with approximately thirty feet of the falling taking place between Barton Mills and Mildenhall. Situated halfway between London and Norwich, the two largest cities in England at the time, there was a great market potential. It is possible that the mills referred to in the name, were floating mills with a paddle beneath them turning the stones. This was common along the Thames and in Italy during this period and would explain why there is no archaeological evidence of great activity. Until Elizabeth researched this history, my entire knowledge of Sir Henry Barton was that he was Lord Mayor of the City of London, at the time of Dick Whittington, and the first Mayor to organise street lighting in London.

Henry Barton died a wealthy man without doubt, leaving a substantial amount to his nephew and the deprived people of the region. However, if his bequest of three hundred pounds to the poor of Mildenhall could conceivably be read to support my embarrassing distant relations; everything that Elizabeth has written above falls into place with the stories I gleaned, with difficulty. I am therefore certain of their accuracy. On his death his wife was considered wealthy with a legacy of £159. My mother would never discuss the antecedents of her grandfather, James Barton. She always said we were poor relations and an embarrassment. My aunt Ruby, whom many will remember as the head mistress of Upware School, was equally unforthcoming. Indeed when artist Anthony Day showed her a photograph of James Barton working, she refused to look at it. For many years all I had heard was that he was a widower with two young children and he married Adelaide Adamson Woolard, who was alone in the world and despite her relative wealth needed someone to ‘protect her’.

Woolard Barton, their youngest son had an older sister Jessie. I had been told that she was so beautiful that when working as a companion to a lady of title in London, a man of great wealth came in the room and virtually proposed on the spot. This was hard to believe until a chance meeting with a descendant of the two step children, told me they were related to one of the great beauties of our time. There were ten Remington children but I only ever met one, Ella Remington. She was very memorable, elegant and aristocratic with every movement and dressed in style. We first met when she came to lunch at the Mill House in Soham, now demolished, accompanied by Ruby Barton, I was seven years old. My brother and sister ate with the family but I usually ate with the maids. I walked in to be greeted by, ‘Here comes the ugly duckling’. I had never met anyone who was such fun before and our association continued until I went into the air force when I was eighteen. She told me of her social life, before she decided to elope with an Irish doctor. Ruby Barton said she had to because she had run out of time! Anthony Day also loved her visits to Wicken when he was a child, for all the fun she brought into his life. She became the principle source of most of my knowledge of these stories. Mr Wick Alsop, president of the 99 Rowing Club and Social Director of Pyes Radio in addition to his banking; had re roofed Wicken Church in memory of his mother, who was another sister of Woolard Baton, said that whenever he was involved with Woolard Barton, it was like a party because he laughed so much.

The main story ran like this… James Barton decided to leave Tuddenham and having married a Harvey, who died young leaving him with two young children, he finished up in Wicken as an agricultural labourer. Adelaide Woolard, like him, had had a grand background but was now in need of protection with no living relations and a young child to care for. She was comfortably off for the time with the remains of her inherited wealth. They decided however to make their lives together and over the years she educated him. On their wedding day, he went to church to marry her after ploughing all morning, arriving in his working clothes. Despite this she gave him a gift, a watch with the name James Barton on instead of numerals. The marriage worked and in addition to the aforementioned children, there was another girl called Hagar who did not marry. She kept the Wicken tradition of being a lady by walking her dog in the morning. Of Julius, another son, he was known to have had an adventurous life and went to London to live.

The death of my mother’s brother Wilfrid, reputed to be one of the handsomest men of the area when young, meant the end of the Barton family in Wicken after approximately 200 years of residence. People always considered them one of the oldest Wicken families, but in actual fact despite the silence from my relatives they were really based in and around Mildenhall, where strangely my only daughter now lives.

Family associated piece kindly supplied by Mr Timothy Clark.